Heavy Words

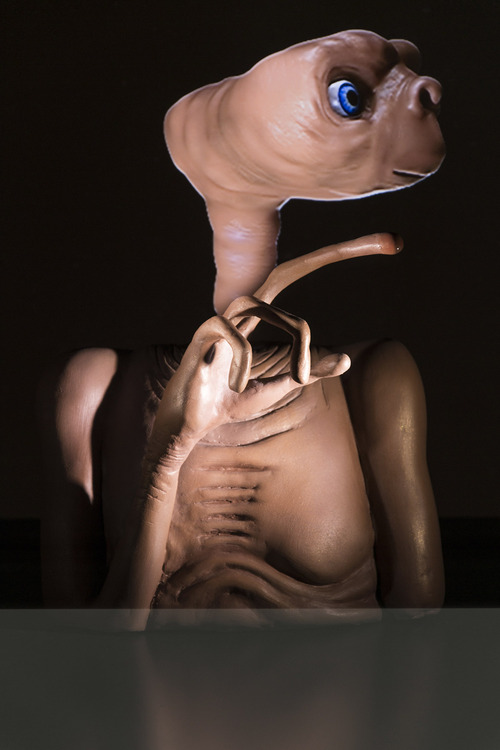

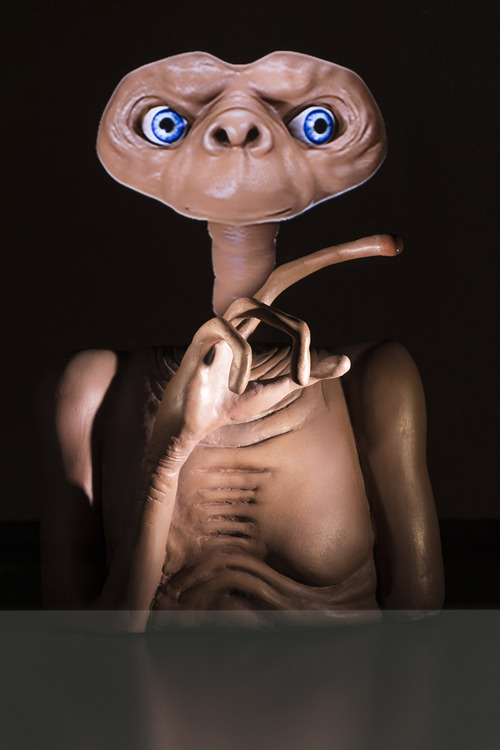

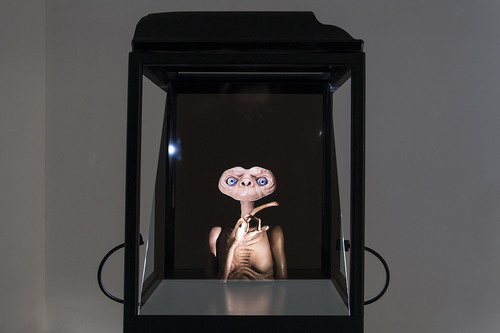

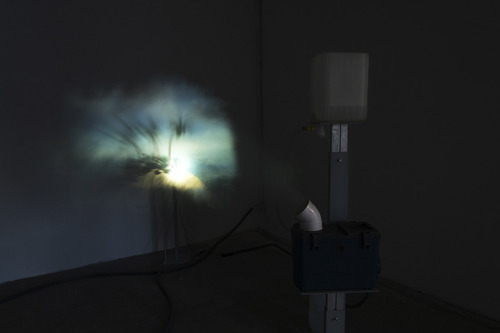

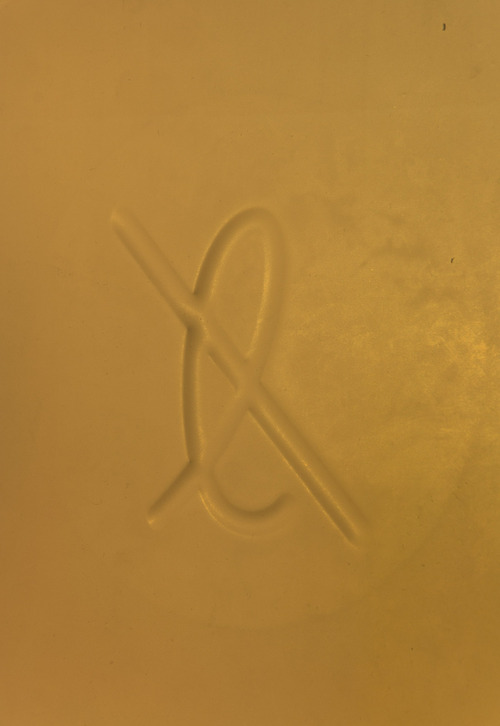

| Heavy Words @ Peep-Hole The exhibition was composed of trilogy of recent works around the three way material equivalence words - images - objects. The works included Il Etait Une Fois, Image Families, and Abracadabra. It was curated by Florence Derieux at Peep-Hole in Milan. Below is the text for the exhibition for the Speculations on Anonymous Material, Nature After Nature, Inhuman catalogue. The exhibition showed Image Families, which was also part of Heavy Words. HARD FEELINGS / CYBORG WORDS The symbiotic machines started accumulating data on the people that used them. Heart rates, GPS coordinates, pictures, conversations, videos, sleep patterns, ingested calories, social interactions, Internet searches … desires, thoughts, biorhythms. And the greedy utopians who wanted to better the lives of inter-connected global village inhabitants pushed the machines to collect more data every day. The machines got to know you better than anyone else, better than your parents, down to your darkest fantasies. These machines, the mainframe computers that gathered all the collected data, operated by the techno-commercial conglomerates, started to churn out goods and services precisely tailored to each individual. Individually tailored food, clothes, playlists and romances. Imagine that in this world of custom consumerism a new product were to come to market: a portable piece of equipment that could print out small feelings-objects for every moment of your life. -“I feel a little strange. Look, it has legs, the body is square with what looks like, what … caramel, gooey caramel-like paste inside. I’ve never seen anything like it before.” She was talking about the new print that came out of her feelings printer. A neat little device that analyzed her feelings and in return printed out small, odd objects meant to represent her emotions. The printer would trigger a print whenever the machine deemed the feelings interesting enough to output. Designed by hacker communities, the printers were cheap to buy and operate, yet could output a wide variety of materials, liquid or solid. As a result the prints were often strange looking. This one was truly peculiar. -“Why don’t you get one?” -“What? A printer?” We had been talking about the death of her father and our nascent relationship—we had just met As we were talking, the result came out of the device. The printer followed a specific algorithm, tuned to each individual. The output’s shape and materials was based on one’s emotions, their complexity and intensity. The printed feelings, the object, looked different each time. Our conversation digressed. -“Yeah. Why don’t you get one?” -“I don’t see the need for it. I am already woken up when I need to be—because my sleep patterns are processed by my alarm clock—and my email provider automatically books my travel plans by skimming through my emails. I receive new music daily. I get constant suggestions for new restaurants that I end up loving. The machines already know me really well and cater to all my needs. So really, I don’t get your feelings printer, because frankly I don’t need it.” -“But what you describe is companies catering to your needs. It’s horrible that a company comes up with anything you want before you even know you want it.” -“I have no problem whatsoever with corporations coming up with goods for me. It’s all great stuff. As long as the machines’ algorithms figure out what I want and do it right. It’s like being an infant again. I am fed, dressed and kept entertained, effortlessly. I want to live like a baby forever!” -“But you’re missing out on expressing what you want, on addressing your desires and feelings. You cannot possibly let machines run by corporations do that for you! This infantilization is a real problem. Machines sit at the center of all human interactions. I speak through a machine that then talks to you.” -“What do you mean? We are not talking through a machine now.” -“I don’t mean you and me now; I mean that machines—as in smart phones, computers, tablets, smart watches, you name it—are used to transmit most conversations, video, voice or text-based. Only on a few occasions the machines are not the mediators. And even then, when that’s not the case, when the machines seem silent, they’re still harvesting.” -“So what? We live surrounded by machines that eavesdrop on us? The data these machines collect are used, amongst other things, to predict what people want. But your printer is no different than what the corporations already do. Your printer still spies on people. The feelings printer works very much like my music provider, except instead of giving me things I want, like music, your printer outputs something that I don’t care about, some small object made out of half caramel, half metal. It’s basically useless. As expressing my moods, like I said, the music I am sent daily reflects my mood just fine, and so does this custom T-shirt I am wearing. The items that the machine-corporations—or whatever you want to call them—offer me, suit me perfectly well.” -“They fill a void. These items, the goods or services you’re talking about are real and tangible, but they are just things that fill a gap. My feelings printer expands on this void. The printer is not looking to plug the void. The feelings-objects it prints are strange, open and left to interpretation. They are opaque, unlike the goods that corporations feed you.” -“What do you mean?” -“The void is important. It’s a necessary self-discovery tool.” -“What void are you talking about?” -“The endless deficiency that obsessive consumerism generates. The insatiable hole that one can never fill up.” -“Hang on … so you see your feelings printer as some kind of social tool?” -“Yes, an educational role of some sort. You and I can talk about this weird object that comes out of the printer, this caramel goo with spider legs. When we talk about it, we talk about feelings. That’s why it is important for the printer’s output to be an object and not a perfume for instance. There must be something tangible to talk about or talk through. There is a trick that child psychiatrists use when they consult children who are able to talk but refuse to–because kids don’t go to the shrink of their own volition. Kids sometimes don’t want to talk, or they have speech blockages. One thing shrinks do in these cases is to hand the kid a toy plastic phone. The shrink grabs one too and the two strike up a conversation. The kid who was reluctant to talk gets going. He or she talks through the phone to the shrink. It’s a transference phenomenon. This is pretty much what the feelings printer is about: It is a transference device in today’s world.” -“Hmm … but why do you think people need to talk about their emotions?” -“Because the more you talk about feelings, the more you know feelings. One can argue that new communication technologies allow people to be freer, to discover themselves. I would argue the exact opposite, that the vast majority of the population is losing touch with their emotions, and everyday a little more. I know that this is not a representative sample by any means, but my friend Shana, for instance, every time I ask her how she feels, she replies, “I don’t know.” And if I ask her, “You don’t want to tell me how you feel, or you really don’t know how you feel?” She replies, “I really don’t know.” She’s not the only person around me like that. People are numb. People lack a certain form of empathy, or at the very least basic interpersonal communication skills.” -“Well, for sure, your friend Shana does sound like she is not in touch with her feelings. But that could be something else all together. Your friend sounds like she is affected by alexithymia–the difficulty of people to perceive and describe emotions of others and themselves. Alexithymia supposedly affects about ten percent of the population, in various degrees. It is linked to autism. I know of alexithymia because a friend of mine was diagnosed with it.” -“I didn’t know about alexithingy.” -“Nobody does strangely. And by the way you can count me as one of your detractors. I think these new technologies do liberate people to become freer, to explore who they truly are. That’s because the machines know of people’s desires. The machines encourage people to express their true nature. But I hear your point though. I too have heard that same complaint, that people are not that good at dealing with emotions. It’s clearly debatable because how do you measure feelings in people? What is the metric for feelings and their expression? Let’s say for the sake of this conversation that it’s true: let’s say that people are losing touch with their emotions. What is really the problem with people losing touch with their feelings?” -“What do you mean, what’s the problem? Are you kidding?” -“No, I am serious. What’s the problem with people losing touch with their emotions? Or another way to ask this question: How do you think it happened that people lost touch with their feelings?” -“How it happened? How did people lose touch with their feelings? There are many factors combined. You could write the scenario like this: first people got plugged into machines. They saw the world through machines, they talked through machines and now the people desire through machines. Machines have developed palliative capabilities, they can think and feel for people. But this is not the problem. The assistive technology we are talking about—the technology that enables the machine-corporations to come up with a T-shirt that you want without you even saying that you want it—was designed here in the US and is grounded in Protestant puritanism. I believe that technologies, or rather the underlying concept behind each new technology are firmly grounded in the remnants of creepy religious morality. It makes sense that the underlying repressive forces of religion also operate through technology, especially technology used to communicate. It may be a digression, but I see that the fantastic technology you so praise is littered with religious bigotry, that’s one problem. The other problem is that this assistive technology is mostly developed for socio-economic purposes–ultimately this machine-corporation ecosystem sells goods. Here people’s desires equate goods, and capitalism is a destructive force. It’s both religion and capitalism that make people numb and these technologies enable and accelerate the process.” -“Wow. There are so many debatable points in your argument that I don’t even know where to start. You think religion has to do with the way computers design my shoes? Come on … And you don’t really answer my question, what is the problem with people losing touch with their feelings?” -“The problem? It has to do with cyborg words.” -“Cyborg words?” -“Well, language is no longer solely used by humans; it belongs equally to machines, the symbiotic machines that we created. Words are part human, part machine. Words are cyborg words.” -“…” -“I bet you that for every disappearing human language, a new computer language is created, as in code language. For instance Arbëresh. The last person speaking Arbëresh, some Albanian dialect spoken in Italy, dies and on the same day Apple announces Swift a new proprietary programming language.” -“So?” -“This is what these feelings printers are all about. All these relatively new communication technologies were anticipated to have a massive impact on society: surveillance, privacy, labor, information dissemination, etc. And this is of course true, all these technologies—as in Internet 2.0, 3D scanning, smart phones, predictive intelligence—affect society massively. But now there is a group of people, searchers, thinkers, activists, hackers who believe that the technologies have deeper, more pernicious implications than initially anticipated. The technology deeply affects language and how we perceive objects and reality. Basically this group of people posit that the transformation to a symbiosis between humans and machines is fully under way. Not necessarily because humans have become cyborgs, but because the machines have become more human. This group argues that the symbiotic machines—this giant corpus that we, humans, have created to serve us—is a cyborg. The body of all machines combined, from smart phone acting like antennas to mainframe computers–the giant server farms, collecting and analyzing all data—this machine corpus is incredibly apt and more meshed with our lives than we first thought. It is a part-machine, part-human entity. In turn, anything human is becoming part machine, since we are so dependent on the machines. The logic of the feelings printer is not to go against the transformative powers of these technologies, but to bring yet more complexity to the machines, to feed the ecosystem. And in doing so, in what is most important to me, the feelings printer leaves monetary exchanges out of the equation. The printer exchanges goods for rare objects, shoes for printed gooey caramel, airplane tickets for polished blocks of metal. It leaves goods and corporations out of the inter-human interactions.” -“I am not sure I like what you see.” -“…” -“… and you know what’s ironic?” -“What?” -“We completely stopped talking about the death of your father.” I reached out to her hand as I said it. -“Oh well, at least I have this object to remember how I felt about him on a day like today. It’s better than a picture.” |

|